Some medical breakthroughs arrive with fanfare—antibiotics, vaccines, surgical innovations that change everything overnight. Others work quietly in the background for over a century, saving lives without anyone noticing.

Meet methylene blue: the 148-year-old dye that keeps reinventing itself, solving problems its discoverers never imagined, and teaching us that sometimes the oldest medicines become tomorrow’s cutting-edge treatments.

This is the story of a remarkable molecule that refuses to retire.

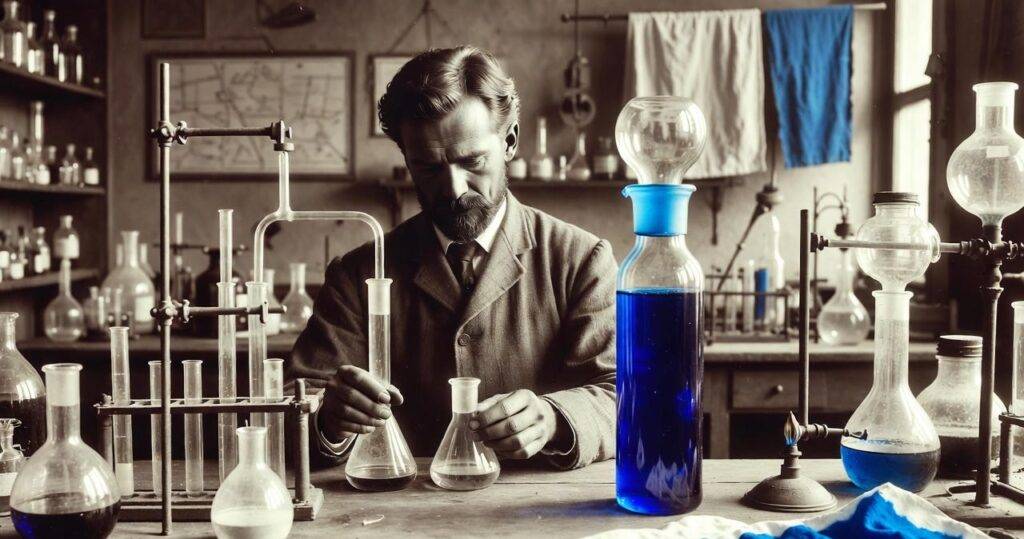

The Accidental Beginning (1876)

Heinrich Caro, a German chemist working for BASF, wasn’t trying to create medicine. He was making dyes for the textile industry—specifically, trying to create vibrant blues for fabrics.

What he created was the first fully synthetic dye: methylene blue. At the time, this was revolutionary for fashion, not medicine. Beautiful blue cloth, mass-produced affordably.

But a young scientist named Paul Ehrlich noticed something strange. When he used methylene blue to stain tissue samples for microscopic examination, it didn’t just color everything uniformly—it selectively bound to certain cells and structures, highlighting them with remarkable specificity.

This selective binding was unusual. Most dyes distributed randomly. Methylene blue seemed to “choose” where it went.

Ehrlich asked a question that would echo through 150 years of medicine: If methylene blue can selectively stain specific cells in dead tissue, could it selectively target those cells in living organisms?

The answer would transform medicine.

First Medical Revolution: Fighting Malaria (1891)

Within fifteen years of its discovery, methylene blue became the first synthetic drug ever used to treat human disease.

Ehrlich and his colleagues tested methylene blue against malaria, one of humanity’s oldest killers. The parasite Plasmodium causes malaria by invading red blood cells. If methylene blue could stain those cells preferentially…

It worked.

Patients given methylene blue saw their fever break, their parasites cleared, their lives saved. It wasn’t perfect—it had side effects, and more effective antimalarials would eventually replace it—but it proved a revolutionary concept: synthetic chemicals could cure infectious disease.

This launched the entire pharmaceutical industry. Every medication you’ve ever taken traces its conceptual lineage back to this moment: a blue dye curing malaria.

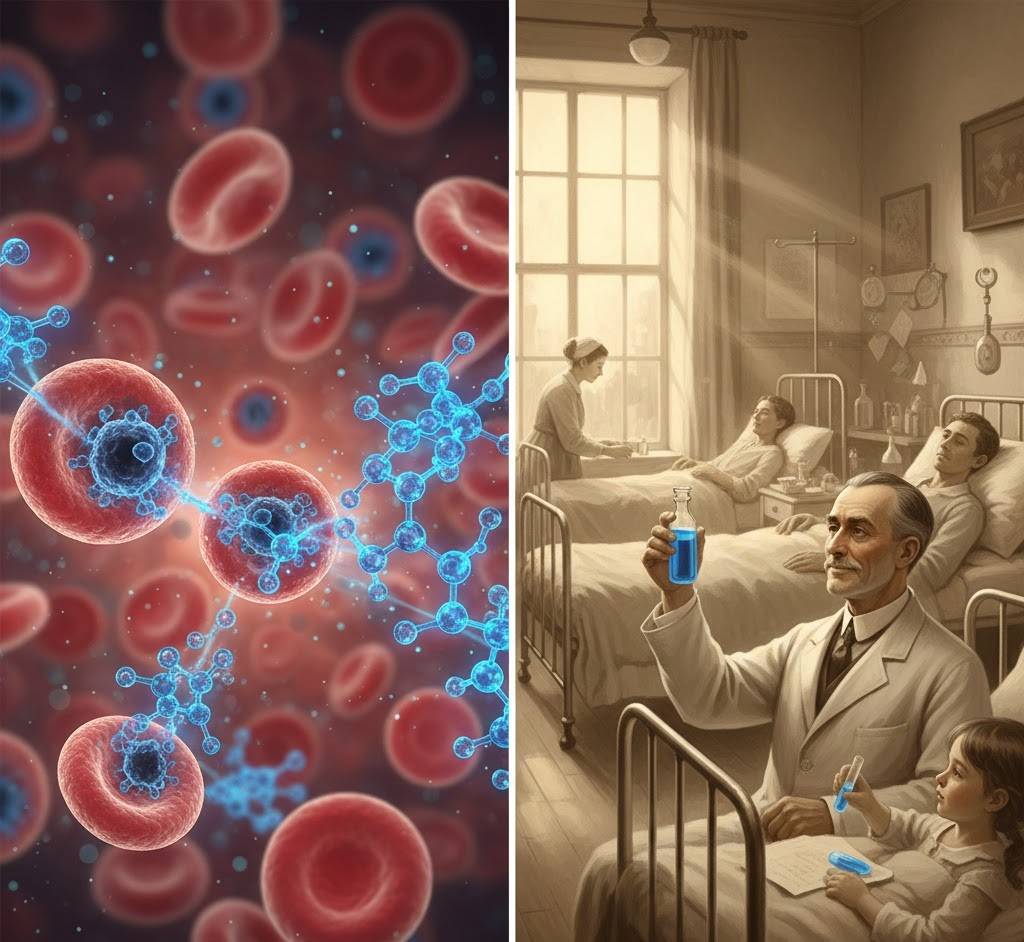

The Methemoglobinemia Solution (1933)

Methylene blue found its next calling accidentally, through tragedy.

When patients arrived at hospitals with blue-tinged skin, struggling to breathe despite having oxygen available, doctors were baffled. The condition—methemoglobinemia—occurs when hemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying protein in blood) gets chemically modified and can’t release oxygen to tissues.

You suffocate despite breathing. Your skin turns blue from oxygen-starved blood.

Someone remembered that methylene blue affects blood cells. They tried it.

The transformation was dramatic. Within minutes, blue-skinned patients turned pink as their hemoglobin normalized. Oxygen flowed again.

To this day, methylene blue remains the first-line treatment for methemoglobinemia—both inherited forms and cases caused by certain drugs or chemical exposures. Emergency rooms stock it specifically for this purpose.

A 90-year-old treatment still saving lives daily—because sometimes, the old ways work best.

Surgical Mapping and Cancer Detection (1960s-Present)

Surgeons face a recurring nightmare: cancer hiding in plain sight.

When removing a tumor, they need to ensure they’ve removed all malignant cells—but cancerous tissue often looks identical to healthy tissue. Miss even a small cluster, and the cancer returns.

Methylene blue offered an elegant solution. Injected near tumors, it preferentially accumulates in certain cancer cells and lymph nodes, turning them blue. Surgeons can see exactly what needs removal.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy revolutionized cancer surgery using methylene blue. Instead of removing dozens of lymph nodes to check if cancer spread, surgeons inject blue dye near the tumor. The first lymph node to turn blue—the “sentinel node”—is the one cancer would reach first. Remove and test it. If it’s clean, the rest probably are too.

This technique reduced unnecessary surgery, shortened recovery times, and improved outcomes for breast cancer, melanoma, and other cancers.

But methylene blue’s cancer connection runs deeper. Recent research shows it may directly kill certain cancer cells, enhance chemotherapy effectiveness, and protect healthy cells from chemotherapy damage.

The 148-year-old dye is becoming a 21st-century cancer treatment.

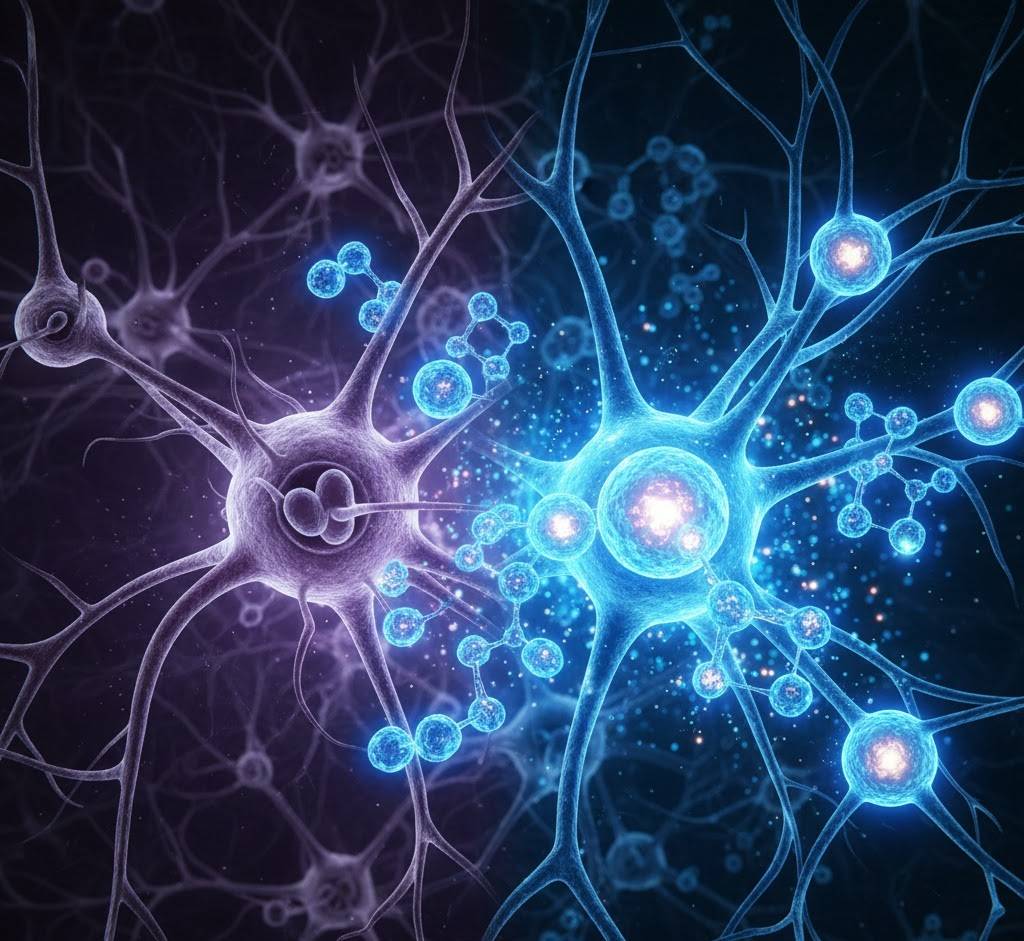

The Brain Connection: Neuroprotection (1990s-Present)

Perhaps methylene blue’s most exciting evolution involves something its discoverers couldn’t have imagined: protecting and enhancing brain function.

Research in the 1990s revealed methylene blue’s remarkable effects on mitochondria—the cellular powerhouses generating energy. It enhances mitochondrial function, helping cells produce more energy more efficiently.

The brain is the body’s most energy-hungry organ. When brain cells can’t generate enough energy, cognitive function declines. In Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, traumatic brain injury, and stroke, mitochondrial dysfunction plays a central role.

Could methylene blue help?

Early clinical trials suggest yes:

- Alzheimer’s patients showed slowed cognitive decline

- Stroke victims had better recovery when treated with methylene blue

- Traumatic brain injury patients showed improved outcomes

- Healthy individuals demonstrated enhanced memory and attention

We’re still in early research stages, but the mechanism makes sense: improve cellular energy production, improve brain function.

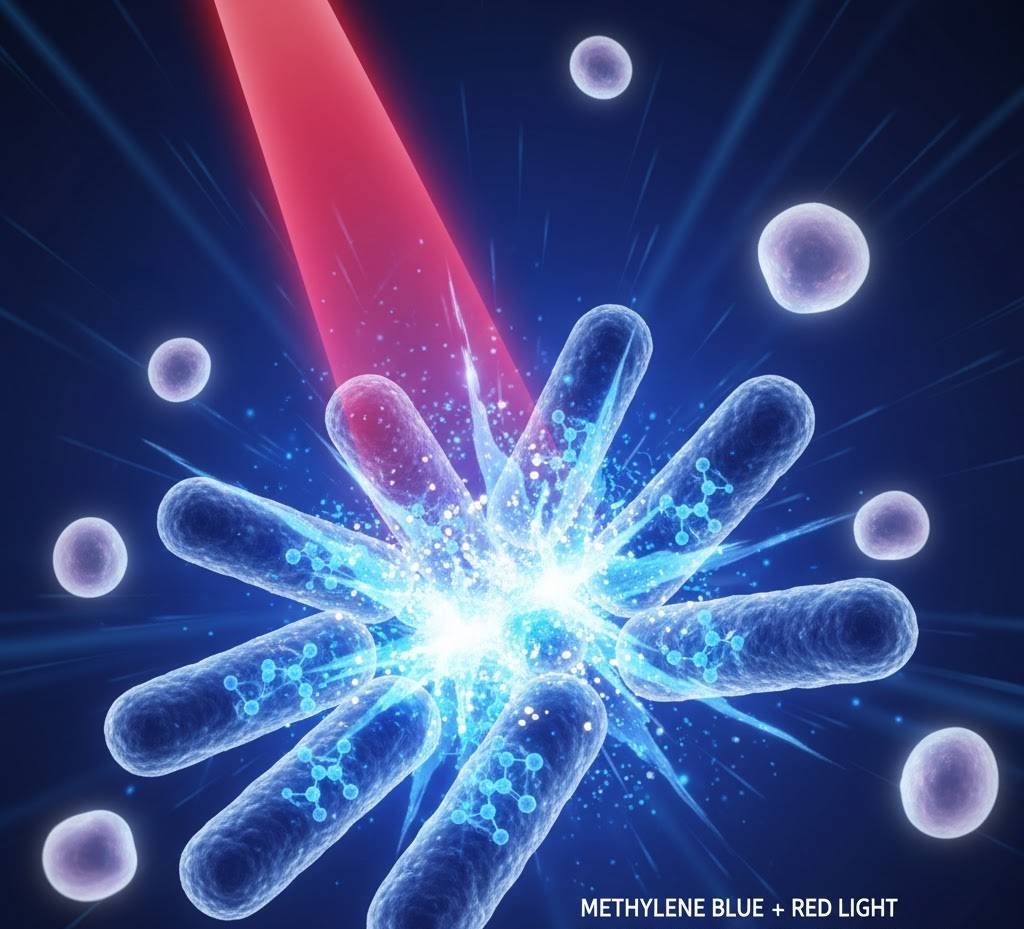

The Antimicrobial Renaissance (2000s-Present)

As antibiotic resistance threatens to return us to a pre-antibiotic era, researchers are desperately seeking alternatives.

They’re finding one in methylene blue—again.

Photodynamic therapy combines methylene blue with light. The dye accumulates in bacteria, viruses, or fungi. Expose them to red light, and methylene blue generates reactive oxygen species that destroy the pathogens without harming human cells.

This approach works against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including MRSA. It treats viral infections including herpes and HIV (in blood products). It eliminates fungal infections resistant to traditional treatments.

Blood banks use photodynamic therapy with methylene blue to sterilize blood products, preventing transmission of viruses and parasites through transfusions. Millions of transfusions are safer because of this 19th-century dye.

Dentists use it to kill bacteria in infected gums. Dermatologists treat acne with it. The applications keep expanding.

COVID-19 and Beyond (2020-Present)

When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, researchers tested everything with antiviral potential.

Methylene blue appeared on the list.

Early studies showed it could inactivate SARS-CoV-2 in laboratory settings, particularly in blood products. While it didn’t become a COVID treatment, it helped ensure blood supply safety during the pandemic.

But the real lesson was broader: This 148-year-old molecule still has relevant antiviral properties in the 21st century.

The Cognitive Enhancement Controversy

Perhaps most controversially, methylene blue is being explored as a cognitive enhancer for healthy people.

Small studies show improved memory, faster reaction times, and enhanced attention in people taking low-dose methylene blue. The mechanism—improved mitochondrial function—is well-established.

This raises profound questions: Should we use medications to enhance normal cognition? Where’s the line between treatment and enhancement? If a drug is safe and effective, why restrict it?

These aren’t new questions, but methylene blue brings them into sharp focus.

Modern Formulations and Delivery

Today’s methylene blue isn’t just the simple dye Caro created in 1876.

Modern pharmaceutical companies have developed:

- Pharmaceutical-grade formulations with precise dosing

- Nanoparticle delivery systems targeting specific tissues

- Combination therapies pairing methylene blue with other drugs

- Topical preparations for skin conditions

- Sustained-release formulations for chronic conditions

The basic molecule remains unchanged, but how we use it has evolved dramatically.

Safety Profile: 148 Years of Data

One advantage of such an old medication? We have nearly 150 years of safety data.

Methylene blue is remarkably safe at therapeutic doses. Side effects are generally mild—temporary blue-green discoloration of urine (startling but harmless), occasional nausea, and rare allergic reactions.

Serious side effects are uncommon but include interactions with certain antidepressants and rare cases of serotonin syndrome. But compared to newer drugs with unknown long-term effects, methylene blue’s extensive track record is reassuring.

This safety profile enables researchers to explore new applications with confidence.

The Future of an Ancient Drug

What’s next for methylene blue?

Current research explores:

- Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s treatments with larger clinical trials

- Anti-aging therapies targeting mitochondrial decline

- Cancer combination treatments enhancing chemotherapy

- Antiviral applications for emerging diseases

- Athletic performance enhancement through improved cellular energy

- Longevity research investigating lifespan extension

Some may prove effective. Others may fail. But the pattern is clear: every generation rediscovers methylene blue and finds new uses for it.

Why Old Drugs Matter

Methylene blue’s story teaches valuable lessons:

Sometimes answers hide in plain sight. We don’t always need new molecules—sometimes we need new perspectives on old ones.

Mechanisms matter more than origins. Whether a drug was discovered in 1876 or 2024 is irrelevant if it works.

Drug repurposing is powerful. Developing new drugs costs billions and takes decades. Repurposing existing drugs with known safety profiles is faster, cheaper, and lower-risk.

Medical history is a resource. The pharmacological past contains forgotten treasures waiting for rediscovery.

The Remarkable Persistence of Usefulness

In an era of cutting-edge biological drugs, targeted therapies, and personalized medicine, it’s humbling that a simple synthetic dye from 1876 remains clinically relevant.

Methylene blue has survived and thrived through:

- The antibiotic era

- The chemotherapy era

- The biological drug era

- The precision medicine era

It persists because it works—simply, effectively, safely.

This 148-year-old molecule isn’t finished yet. Its next medical revolution might be just beginning.