We all carry the same quiet curiosity: How did lifeless chemistry turn into the first creature that could feel hunger, fear, or the warmth of sunlight? The scientific quest to answer that question is called abiogenesis (literally “life from non-life”) is no longer just philosophy in lab coats. It’s one of the most thrilling detective stories on Earth right now. Here’s the latest chapter, told plainly and with wonder.

1. Earth’s Wild Youth – A Planet That Loved Chemistry

Four billion years ago our planet was a restless teenager: constant meteorite bombardment, oceans of scalding water, and an atmosphere thick with carbon dioxide and nitrogen. It sounds hostile, but to a chemist it was paradise. Every lightning bolt, every hot vent, every crashing wave, and impact crater was running trillions of natural experiments. The raw ingredients for life (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus) were everywhere. The only thing missing was time and a little luck.

2. The Miller-Urey Experiment Never Really Ended

Most of us learned about the 1953 Miller-Urey experiment in school and thought, “Cool, done.” Wrong. Scientists have spent seven decades tweaking the recipe. When they use more realistic early-Earth gases (CO₂, N₂, and traces of hydrogen) plus minerals from meteorites or vents, the yield explodes: all 20 life’s amino acids, sugars, and even the bases that make RNA and DNA appear in days, not weeks. Nature had billions of years and an entire ocean as its flask.

3. The RNA World – When Genetic Code Learned to Copy Itself

RNA is the Swiss-army-knife molecule. In 1986, Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman won the Nobel Prize for proving RNA can act as its own enzyme. Today, labs have created RNA that can copy long stretches of itself without help, evolve new functions in hours, and even build simple membranes. We are literally watching Darwinian evolution happen in a test tube with molecules that have no cells yet. It’s the closest thing we have to witnessing the birth of heredity.

4. Three Birthplaces Walk into a Bar…

Right – a comet nucleus cracking open in space, releasing a tail of water and organic molecules toward a young planet.

All three connected by glowing threads of amino acids and nucleotides, warm vs cold color split, 16:9

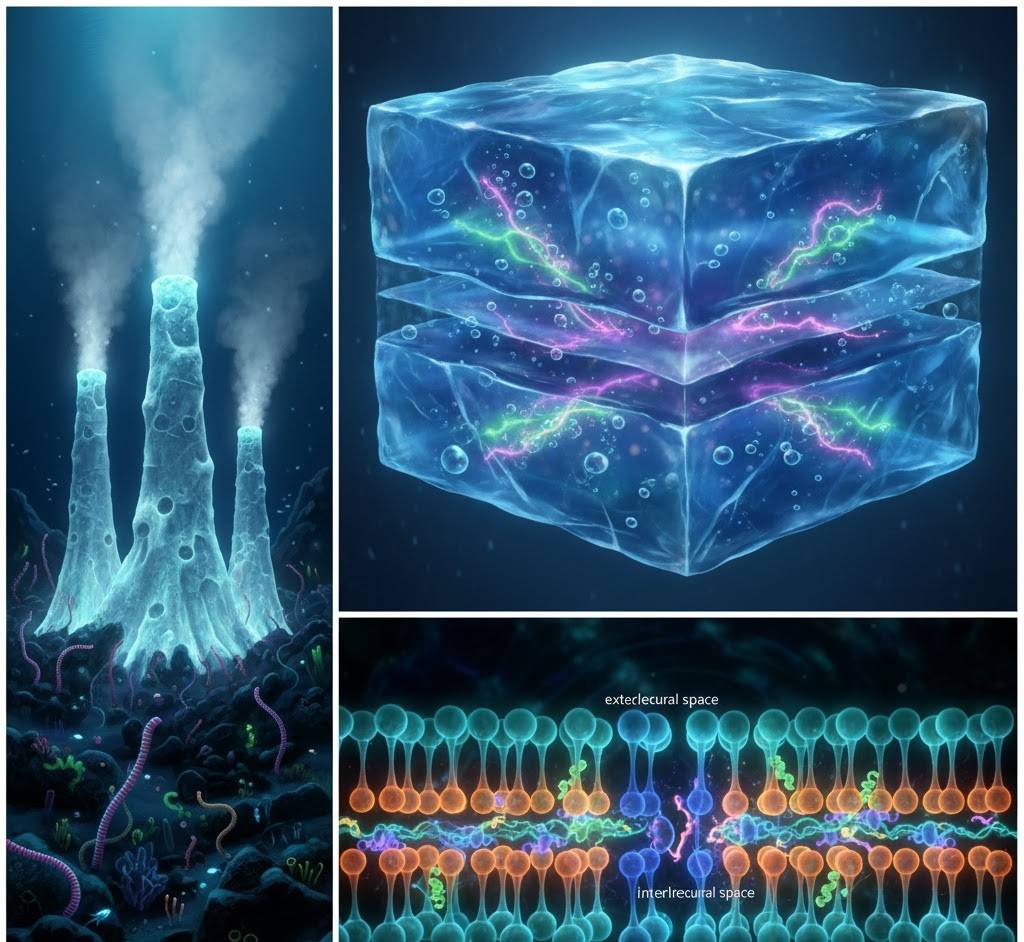

Nobody agrees on the exact address where life was born, and that’s okay. Maybe it was:

- Deep-sea “white smoker” vents where natural proton gradients act like batteries.

- Warm shallow ponds that dried and re-wet, concentrating chemicals.

- Ice surfaces that act like tiny freezers, forcing molecules together.

- Or even comets that delivered the starter kit.

Current betting favorite? Alkaline hydrothermal vents (think Yellowstone under the sea) because they provide continuous energy, mineral catalysts, and natural “cell-like” pores in the rock.

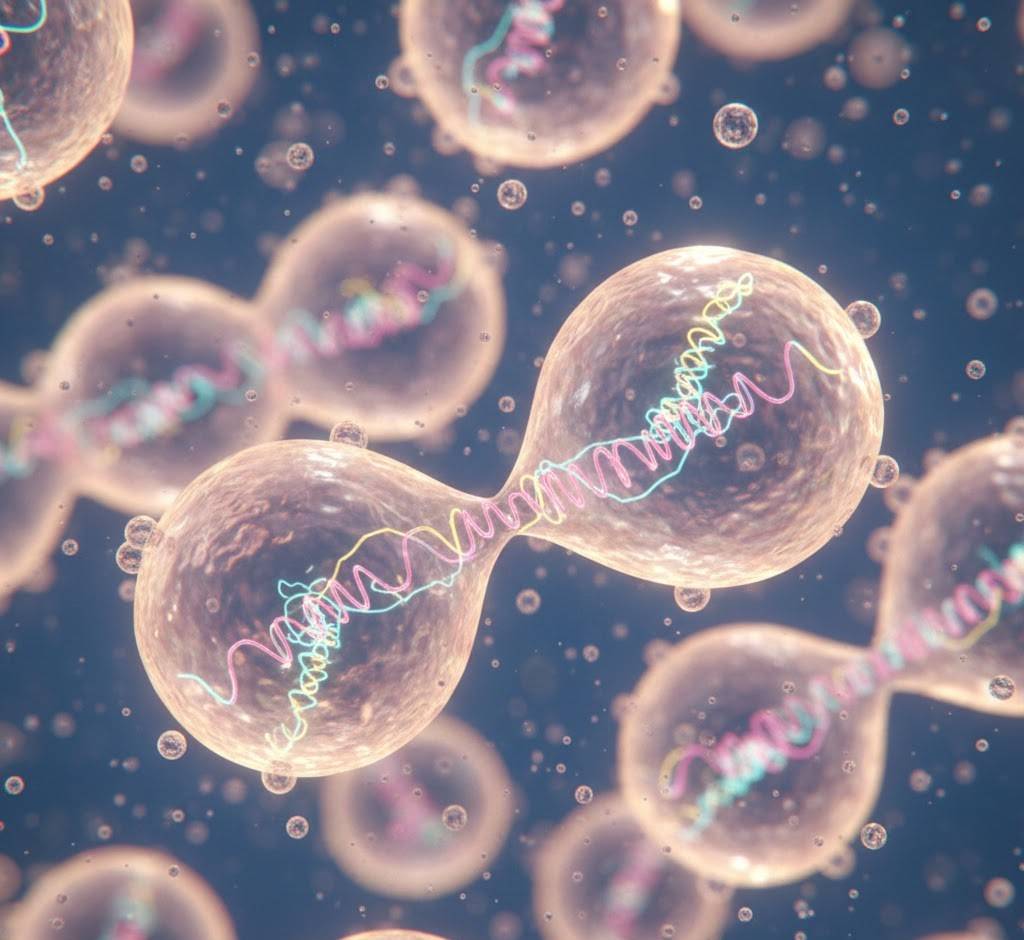

5. The First Cells Were Probably Leaky and Messy

Real cell membranes with phospholipids came later. The first compartments were probably simple fatty acids, the same stuff in soap. They self-assemble into bubbles, grow by absorbing more fats, and split when they get too big. They’re leaky on purpose (good for letting food molecules in) and terrible at keeping secrets (also good, because early life needed to share genes). Community came before individuality.

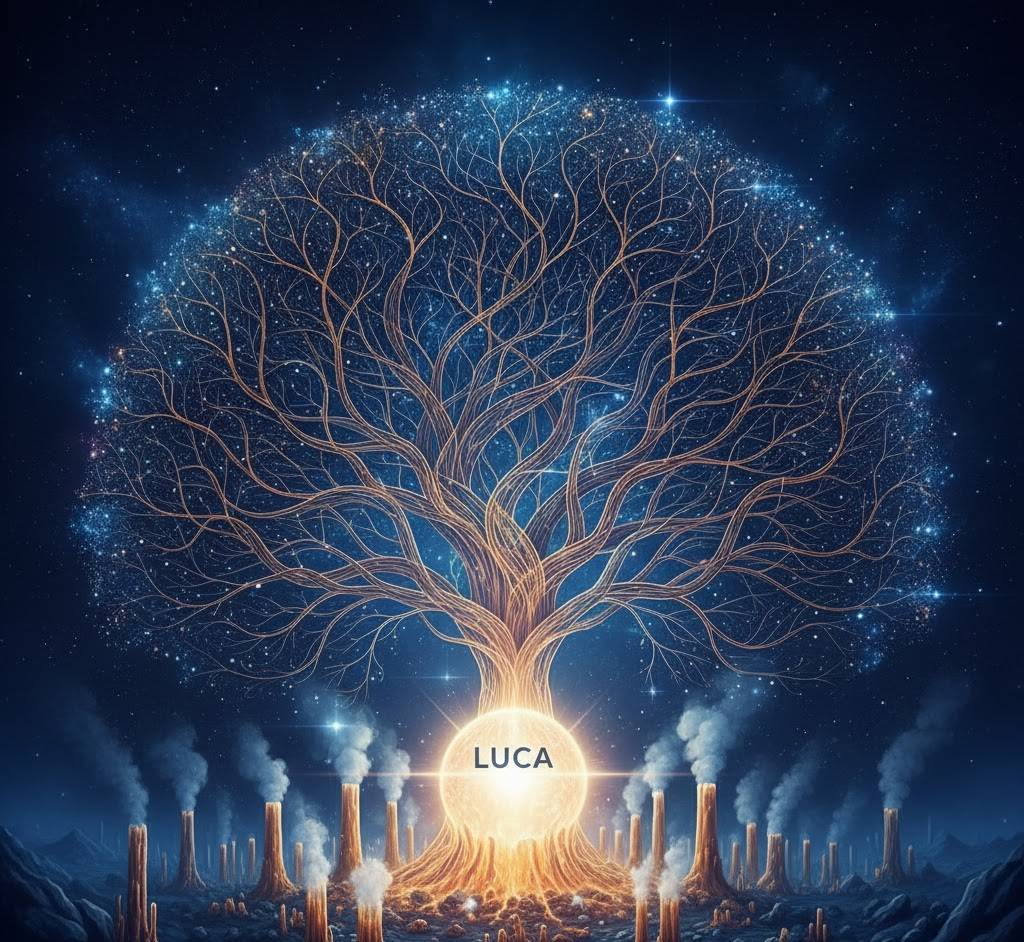

6. Meet LUCA – Your Great×10³⁰ Grandmother

By reading the shared genetic code in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, biologists have reverse-engineered the Last Universal Common Ancestor. LUCA was already a sophisticated single cell with hundreds of genes, ATP energy currency, and a real cell membrane. That means the jump from chemistry to full-blown life happened even earlier, probably 4.2–4.3 billion years ago, when Earth was barely cool enough to hold liquid water.

7. Life on Ice – The Cold Cradle Theory

Ice might sound deadly, but it’s a brilliant chemist. When seawater freezes, impurities are pushed into tiny liquid veins where they become super-concentrated. Add a dash of UV light or cosmic rays and you get rapid reactions. Some researchers now think the first replicating systems may have been “ice RNA” rather than “hot-soup RNA.”

8. Panspermia Lite – We Might All Be Aliens (Sort Of)

Rocks regularly get blasted off Mars, the Moon, or even distant star systems and land here. We’ve already found amino acids and nucleobases in meteorites. Life may not have started from scratch on Earth; it may have gotten a massive head start from space delivery. The chemistry still had to happen here, but the ingredients were express-shipped.

9. Watching Life Begin in Real Time

Today there are labs (like those of Jack Szostak at Harvard, Philipp Holliger in Cambridge, and the Earth-Life Science Institute in Tokyo) where scientists are creating “never-lived-before” chemical systems that grow, divide, compete, and evolve. Some can already pass traits to offspring molecules. We are inches away from creating brand-new life in a test tube, not by playing god, but by letting chemistry do what it has always done.

10. Why This Changes Everything

Understanding abiogenesis does three huge things:

- It tells us life is not a miracle but an emergent property of the universe, likely common wherever there’s water, energy, and time.

- It gives astrobiologists clear shopping lists for Mars, Europa, Enceladus, and exoplanets.

- Most beautifully, it reminds us that every living creature (including you reading this) is family. We are all descendants of the same ancient chemical spark.

The study of life’s beginnings is no longer “how could it possibly happen?” It’s “how many ways can it happen, and how fast?”

We stand at the edge of answering the deepest question humanity has ever asked. And the answer, when it finally comes, won’t diminish the wonder. It will multiply it a billionfold.

Because if life can arise from humble chemistry once, on a half-molten infant Earth, then the universe is probably teeming with it. And every star in the sky is a potential cradle.

We are not just in the universe. We are the universe trying to understand its own reflection.